Table of Contents

What Is Tempering?

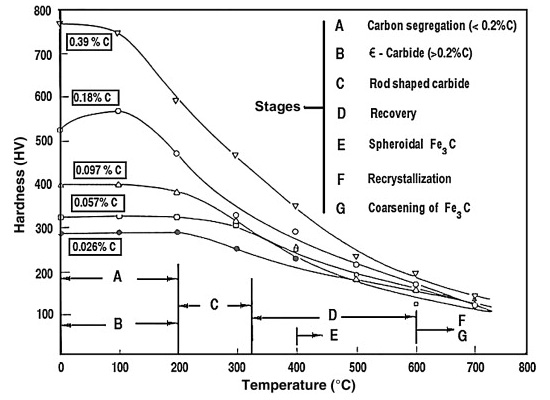

Tempering is a heat treatment process applied to steel and other alloys after quenching. During quenching, metals become very hard but also brittle, which can lead to cracks or sudden failure. Tempering provides a “gentle recovery” by reheating the quenched metal to a lower temperature, then cooling it at a controlled rate.

-

Typical Tempering Temperature Range: 150°C – 650°C (300°F – 1200°F)

-

Heating Mediums: air, oil, molten salt, or protective gas atmosphere

-

Cooling Mediums: usually still air, sometimes oil or water depending on the steel grade

Purpose of Tempering

The main goal of tempering is to balance hardness and toughness. While quenching maximizes hardness, tempering adjusts mechanical properties for real-world applications.

Key Purposes:

-

Reduce internal stresses caused by rapid quenching

-

Improve toughness and resistance to impact loading

-

Enhance ductility so the material is less likely to crack

-

Adjust hardness to match engineering requirements

-

Stabilize microstructure for dimensional accuracy during service

Types of Tempering

Tempering can be divided into categories based on the temperature range and final application:

-

Low-Temperature Tempering (150–250°C)

-

Retains high hardness

-

Used for tools requiring wear resistance

-

Example: knives, cutting blades

-

-

Medium-Temperature Tempering (250–500°C)

-

Balances hardness and toughness

-

Used for springs, shafts, and gears

-

-

High-Temperature Tempering (500–650°C)

-

Produces high toughness with reduced hardness

-

Common for structural steels, automotive components

-

Applications of Tempering

Tempering is used across multiple industries to fine-tune the properties of steels:

-

Automotive: crankshafts, gears, and springs require both strength and shock resistance.

-

Cutting Tools: drills, knives, and dies need hardness but must avoid brittleness.

-

Construction: structural steels for bridges and buildings are tempered for safety.

-

Aerospace: turbine components and landing gear must withstand cyclic stresses.

Real-World Example:

A quenched gear at 62 HRC is too brittle for automotive use. After tempering at 400°C, its hardness reduces to about 50 HRC, while toughness increases, making it durable under repeated loads.

Tempering Furnaces

Box Furnaces (Muffle Furnaces)

-

Enclosed chamber isolates samples from direct heating.

-

Temperature Range: Typically up to 1650°C.

-

Use: Small batches of tools, gears, and lab samples.

-

Cylindrical tube allows placement of rods or long parts.

-

Temperature Range: Up to 1700°C for standard models.

-

Use: Tempering rods, wires, shafts, and research materials; can use protective atmospheres.

-

Sealed, low-pressure chamber prevents oxidation.

-

Temperature Range: Typically 200–650°C for tempering applications.

-

Use: Aerospace components, precision tools, and high-quality steels.

Conclusion

Tempering is the essential follow-up step after quenching, ensuring metals are not only strong but also reliable in daily use. By carefully selecting the tempering temperature and furnace type, engineers can fine-tune hardness, toughness, and ductility to match specific applications.

Whether it’s a precision gear, a cutting tool, or a structural beam, tempering ensures that quenched metals don’t remain brittle but instead gain the resilience needed for real-world performance.

Get In Touch

Fill out the form below — free quote and professional suggestion will be sent for reference very soon!